Some are minor geographic lapses: Tuskegee University is not in Atlanta, but rather Tuskegee, Alabama (322). The problem is that there is evidence of hasty preparation, or more inaccuracies than historians normally expect.

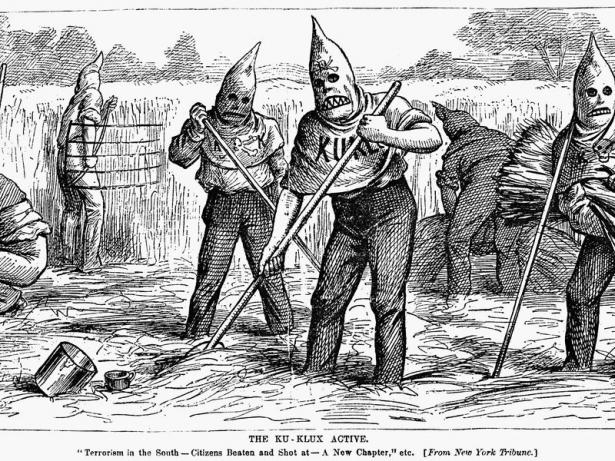

So far, well and good, or at least reasonable. Beyond this, there are interpretive themes throughout, on the interconnection between southern events and civil rights efforts in the North, especially on the black convention movement pressing for drastic change. The stress is on the sheer fact of overwhelming terrorism: how black and white reformers “ultimately lost their fight because of white violence is the subject of this book” (21). Not much attention goes to the variation in terrorist activity in different times and places, how it might have been mitigated or repressed. The emphasis here is on the upbeat early years after emancipation, the laudable aspirations that inspired Radical Reconstruction, and the rampant racism and violence that would, in time, overthrow it. “Too often the central question becomes why Reconstruction failed, as opposed to ended, which hints that the process itself was somehow flawed and contributed to its own passing,” Egerton writes (16). Egerton does indicate that he disagrees with those who emphasize the weaknesses in Reconstruction governance, the divisions within the black community and the Republican coalition.

So thoroughly immersed is Egerton in the prevailing viewpoint that one would expect an explicit discussion of what he hoped to add to Foner. Įgerton’s book follows the modern, sympathetic interpretation of Reconstruction politics without the caveats scholars frequently make about “America’s most progressive era.” It resembles Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988) in highlighting the freedpeople’s story, but without that work’s interpretive grounding in the evolution of the plantation system. But emphatic interpretation combined with inattention to factual detail can complicate even a worthy goal. The book’s subtitle offers a “brief, violent history,” and it delivers on it admirably. The final chapter on recent debates over a proposed Denmark Vesey statue in Charleston makes that clear. The author’s restatement of the core revisionist viewpoint, his attentiveness to the African American experience, and his emphasis on the violence that overthrew Reconstruction are things that some in the public sphere need to hear, yet again. There is something to applaud in this work.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)